There’s buzz around the newly-discovered Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) which is currently out beyond the orbit of Jupiter. It looks like the comet is heading for a very close encounter with the sun next year and could be one of the brightest comets seen in living memory.

This image shows the newfound comet C/2012 (ISON) as seen by the Remanzacco Observatory in Italy. The image, taken by amateur astronomers Ernesto Guido, Giovanni Sostero and Nick Howes, is a confirmation view of the comet, which was first discovered by Vitali Nevski (Vitebsk, Belarus) and Artyom Novichonok (Kondopoga, Russia). Image released Sept. 24, 2012. Credit: Remanzacco Observatory/Ernesto Guido, Giovanni Sostero & Nick Howes

In Nov. 2013, it will pass less than 0.012 AU (1.8 million km) from the surface of the Sun. The fierce heating it will experience could turn the comet into a bright naked-eye object that’s even visible on broad daylight.

Nicknamed “ISON”, the comet’s discovery was announced on Monday (Sept. 24) by Russians Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok, who detected it in photographs taken three days earlier using a 15.7-inch (0.4-meter) reflecting telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON), near Kislovodsk. The new comet is officially known as C/2012 S1.

Much about this comet, and its ultimate fate, remains unknown. Karl Battams of the NASA-supported Sungrazer Comet Project lays out two possibilities: “At this stage we’re just throwing darts at the board…In the best case, the comet is big, bright, and skirts the sun next November. It would be extremely bright — negative magnitudes maybe — and naked-eye visible for observers in the Northern Hemisphere for at least a couple of months.”

“Alternately, comets can and often do fizzle out! Comet Elenin springs to mind as a recent example, but there are more famous examples of comets that got the astronomy community seriously worked up, only to fizzle. This is quite possibly a ‘new’ comet coming in from the Oort cloud, meaning this could be its first-ever encounter with the Sun. If so, with all those icy volatiles intact and never having been truly stressed (thermally and gravitationally), the comet could well disrupt and dissipate weeks or months before reaching the sun.”

“Either of the above scenarios is possible, as is anything in between,” Battams says. “There’s no doubt that Comet ISON will be closely watched. Because the comet is so far away, however, our knowledge probably won’t develop much for at least a few more months.”

When first sighted, Comet ISON was 625 million miles (1 billion kilometers) from Earth and 584 million miles (939 million km) from the sun, in the dim constellation of Cancer. It was shining at magnitude 18.8. That makes the comet currently about 100,000 times fainter than the dimmest star that can be seen with the unaided eye.

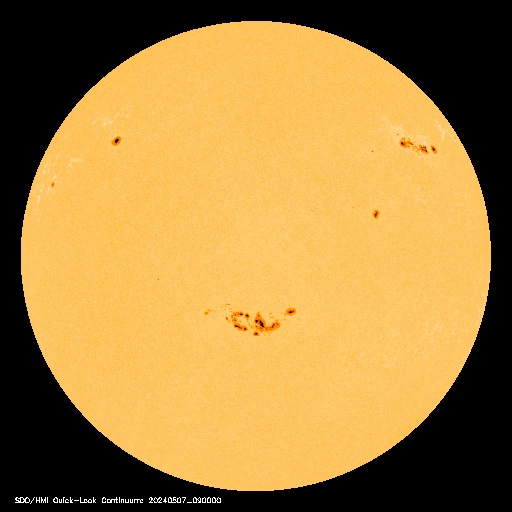

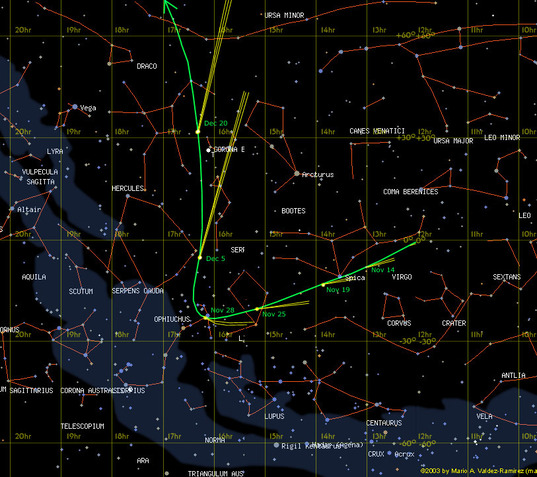

Preliminary track of the comet, via unmannedspaceflight.com member “Gladstoner”

The most exciting aspect of this new comet concerns its preliminary orbit, which bears a striking resemblance to that of the “Great Comet of 1680.” That comet put on a dazzling show; it was glimpsed in daylight and later, as it moved away from the sun, it threw off a brilliantly long tail that stretched up from the western twilight sky after sunset like a narrow searchlight beam for some 70 degrees of arc. (A person’s clenched fist, held at arm’s length, covers roughly 10 degrees of sky.)

The fact that the orbits are so similar seems to suggest Comet ISON and the Great Comet of 1680 could be related or perhaps even the same object.

Comet ISON will be barely visible to the unaided eye when it is in the predawn night sky, positioned against the stars of Leo in October 2013.

This NASA graphic shows the orbit and current position of comet C/2012 S1 (ISON). The comet is at present located at 6.25 AU from the sun, with 1 AU being the distance from Earth to the sun. Image released Sept. 24, 2012. Credit: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory

On Oct. 16 it will be passing very near both Mars and the bright star Regulus — both can be used as benchmarks to sighting the comet. In November, it could be as bright as third-magnitude when it passes very close to the bright first-magnitude star Spica in Virgo.

The few days surrounding the comet’s closest approach to the sun on Nov. 28, 2013, are likely to be most interesting. It will whirl rapidly around the sun in a hairpin-like curve and perhaps becomes a dazzlingly bright (negative-magnitude) object.

The comet will then whirl north after perihelion and become visible during December both in the evening sky after sunset and in the morning sky before sunrise. Just how bright it will be and how long the tail may get during this time frame is anybody’s guess, but there is hope that it could evolve into a memorable celestial showpiece.

Filed under: Comets