Members of the public are being asked to join the hunt for nearby planets that could support life.

Volunteers can go to the Planethunters website to see time-lapsed images of 150,000 stars, taken by the Kepler space telescope.

They will be advised on the signs that indicate the presence of a planet and how to alert experts if they spot them.

“We know that people will find planets that are missed by the computer,” said Chris Lintott from Oxford University.

“When humans have looked at data, we know they find planets that computers can’t.”

Over the nights of January 16-18, 2011, the BBC ran their annual Stargazing event, promoting astronomy to a TV audience with three 1-hour programs each followed by a half-hour discussion and Q&A session. During the first program, Dr. Chris Lintott asked viewers to peruse the data on Planethunters in the hopes that a new planet would be discovered in the data before Stargazing went off air on Jan 18th. That gave viewers 3 days to find a planet.

And find one they did! A viewer who answered the call has helped spot a world that appears to be circling a star dubbed SPH10066540.

The planet is described as being similar in size to our Neptune and circles its parent every 90 days.

Chris Holmes from Peterborough found it by looking through time-lapsed images of stars on Planethunters.org.

“I’ve never had a telescope. I’ve had a passing interest in where things are in the sky, but never had any more knowledge about it than that,” Mr Holmes told BBC News.

“Being involved in a project like this and actually being the one to find something is a very exciting position.”

Chris Lintott who helps organise Planethunters.org added: “We’re ecstatic. We’ve been groaning under the strain of all these people who want to help us, which is exactly how it should be.”

The public participation project was launched last year, but it got a huge boost when it was featured in the popular Stargazing series’ return to BBC Two on Monday (Jan. 16th).

Volunteers have tripled to more than 100,000 people, and the number of images inspected has now reached a million.

The new planet candidate’s status will need more checking, but it looks strong, said Dr Lintott.

“It would be our fifth detection since we started and our first British one as well,” he added.

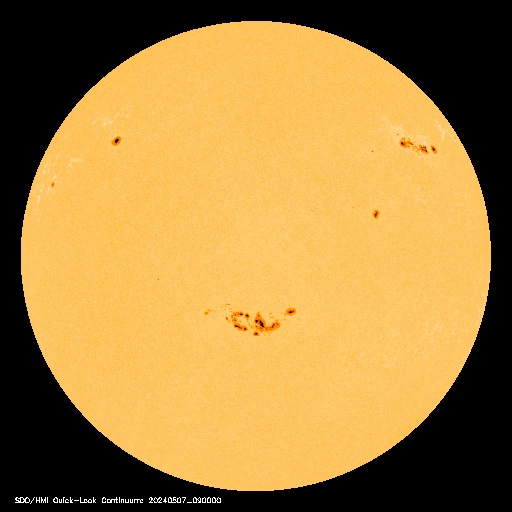

The Kepler space telescope, launched in 2009, has been searching a part of space thought to have many stars similar to our own Sun.

It looks for the periodic dip in light that results every time a planet passes in front of one of those stars.

A tell-tale: A planet passing in front of a star will result in a dip in light detected by Kepler

These so-called transits have to be observed several times before a planet will be confirmed. For the orange dwarf star SPH10066540, five such events have now been seen in the Kepler data.

Mr Holmes found a pass; the Planethunters team then looked deeper into the Kepler archive and found it had made other transits before and after.

The candidate has a radius about 3.8 times that of Earth, and orbits its parent star at a distance of 55 million km – a separation similar to that between Mercury and our Sun.

This means the planet is probably too hot to support life.

“Kepler is trying to answer the question: ‘how many planets are there in our Milky Way Galaxy?'” explained Dr Lintott.

Filed under: Astronomy News